Poo-tee-weet?

Book Review: Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

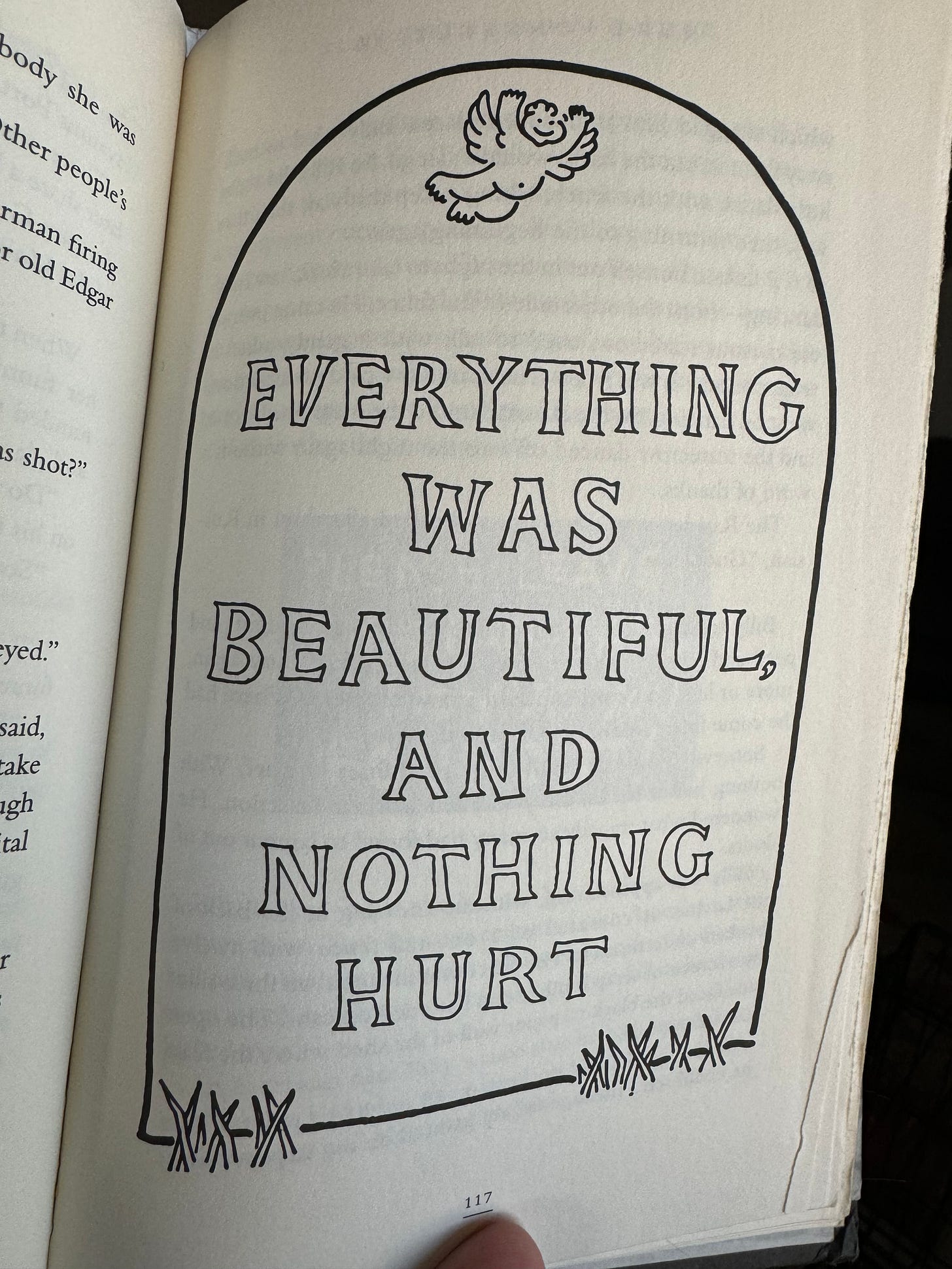

“Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.”

― Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

Genre: Science Fiction, Historical Fiction

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

This is my third reading of this deeply impactful novel. I read it the first time in my 20’s, the second time in my 30’s, and with one year left of my 40’s, I was feeling the pull to read it again for a third time.

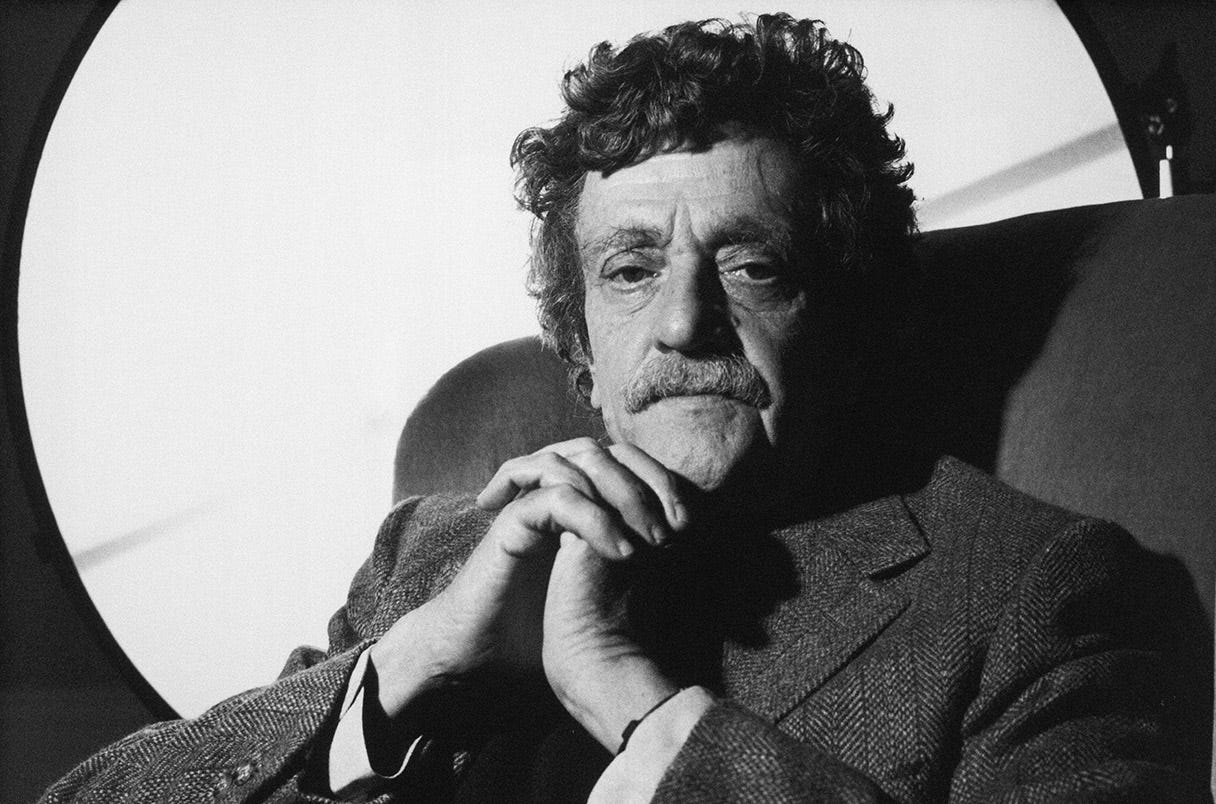

In the first chapter, which reads more like a preface, Vonnegut wants to write a story about the bombing of Dresden in 1945, which he was actually there for as a prisoner of war, but he’s having a bit of writer’s block. He reached out to an old army pal to see if together their reminiscing might produce some fodder for a novel. The man’s wife is clearly displeased with Vonnegut. She thinks he’s going to write another war novel, which will glorify war, thus perpetuating more wars. He promises the wife that he will do no such thing and he kept that promise in Slaughterhouse-Five.

We aren’t introduced to our protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, and his peculiar condition until Chapter 2, which begins:

“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”

Billy is not suited for war. He’s weak, passive, and powerless. His mates ridicule him and treat him like a child, which one might argue, he is—they all are (which is why Vonnegut almost titled it The Children’s Crusade). As a chaplain’s assistant, Billy Pilgrim was not trained as a soldier. He doesn’t even have a gun, or proper boots. He is the opposite of the hero one might expect from a victor’s account of any war—the classic anti-hero. Of all the strong, brave soldiers dying in the war, this scrawny little skidmark survives. It’s absurd.

Freezing in a Luxembourg forest without a proper uniform and disconnected from his larger unit, Billy experiences his first incident of time travel, his own death, which occurs many years into the future. The rest of the story flings poor Billy back and forth indiscriminately into disconnected parts of his past and future so he lives with perpetual stage fright “because he never knows what part of his life he is going to have to act in next.”

He experiences his time in a mental institution, his career as an optometrist, surviving a plane crash, his marriage to a rich, fat lady he doesn’t particularly love, his captivity as a prisoner of war, his childhood, and his abduction by aliens to the planet Tralfamadore where he is kept in a zoo and given an abducted B-list actress with whom to procreate.

This is where he adopts the Tralfamadorian view of life. They do not experience time linearly, but all at once. For example, they know how the universe will be destroyed—they blow it up experimenting with a new fuel for their flying saucers. Billy asks them why they don’t just, you know, not do that. But in their eyes, it has always been that way. They see all of time as one complete picture rather than a string of moments connected by cause and effect. So when someone dies, they only see it as a small part of a much larger picture. There are so many other beautiful moments to focus on. This is the only way Billy can make sense of war.

So it goes.

The narrator says this every time someone dies in the book—106 times to be exact. My feeling is that without these words to emphasize each occurrence of death and destruction, because we have become so numb to it, we might not even notice. In one sense, the phrase itself is like c’est la vie, that’s life, shit happens, oh well. But in another sense, he is very intentionally calling attention to its inevitability. Look at it, he might have said.

Billy does die in this book. He’s murdered but not at the end. He dies early on, because, what even is time? The book ends with Billy’s emancipation from captivity (along with Vonnegut himself). He walks out to view all the destruction the bombing had caused and notices the trees are leafing out—it’s Spring. The last line of the book reads:

“Birds were talking. One bird said to Billy Pilgrim, “Poo-tee-weet?”

It’s a remarkable contrast between humanity’s maniacal compulsion to obliterate life and the faithful continuance of nature. And it reminds us, as the Tralfamadorians have taught us, that there is always something good to focus on. It’s not all death and destruction. You’ll notice there is a question mark at the end of that bird’s chirp. What is the question? What possible answer can there even be?

If you enjoyed this book review, check these out!